For the last twenty-five years, one of my primary areas of focus both in practice and in research has been the ways people learn and the design of environments to facilitate that learning. In the sincere hope that students of all ages will be back on campus soon, the design of learning space is a critical concern. Positive or negative, the design of learning space has a definite impact on the act of teaching and the process of learning.

From the time of Aristotle and Socrates and probably well before that, the primary model for teaching has been based on the idea of a scholar or sage imparting wisdom to those around him. Whether teaching took the form of a lecture or a Socratic dialog, the spaces which developed to facilitate learning were organized with a clear front from which the knowledge was disseminated, and an audience arrayed to passively soak up the erudition.

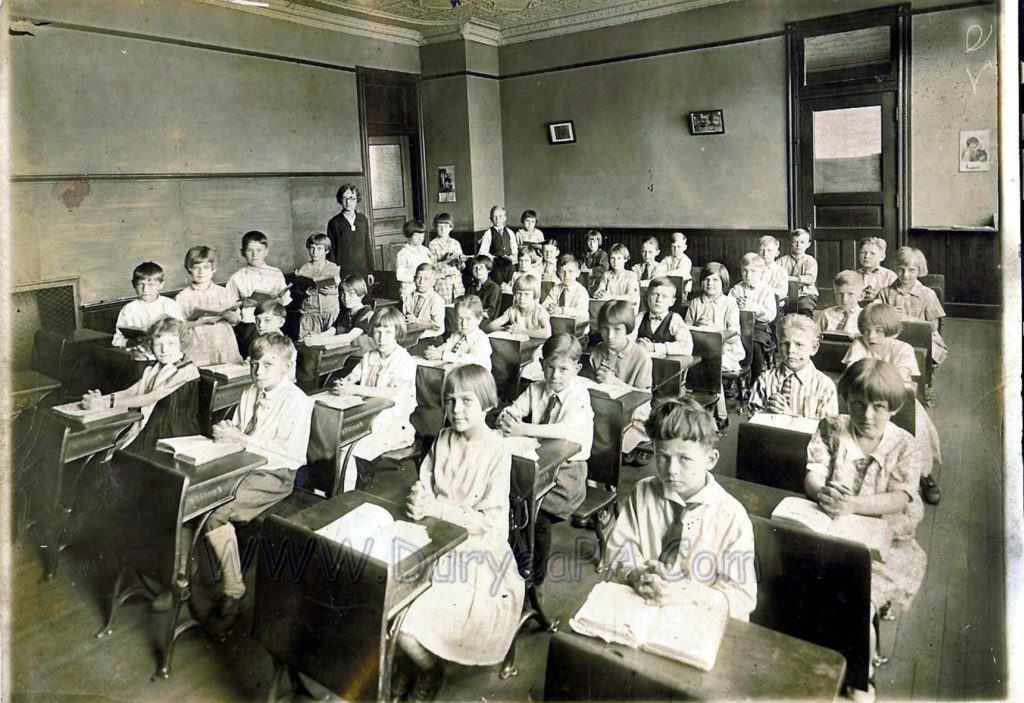

Laurentius de Voltolina’s fourteenth century painting of Henry of Germany delivering a lecture at the University of Bologna (image above) shows a classroom that is almost indistinguishable from many classrooms today, with the teacher seated at a high desk in the front and students seated in forward facing rows. The painting even includes a couple of distracted students having a quiet conversation, and one in the back who is bored and falling asleep.

I guess some things never change.

The dynamics of education changed with the development of the industrial revolution, even if the classrooms themselves did not. When Henry Ford and his contemporaries figured out that they could make things faster if they kept the workers stationary and moved the product past them on an assembly line, they created a demand for factory workers who were trained in a standardized curriculum and could be plugged into the manufacturing process as interchangeably as the widgets they were making. While this did give rise to the public education system in the US and therefore had a huge impact on the number of children who were given the opportunity to go to school, it did not serve the students themselves particularly well.